Uber Strategy Teardown: The Giant Looks To An Autonomous Future, Food Delivery, And Tighter Financial Discipline

The $68B gorilla continues to expand globally in places like India and Brazil and is still chasing autonomous driving. However, it will have to stem its losses ahead of an eventual IPO, which may lead to rollbacks in contested regions like Southeast Asia.

Uber is known for many things, but one thing that has remained constant is its ability to steal the spotlight. Once the darling of tech media, one of Silicon Valley’s most lauded growth stories, and the progenitor of an entire category of on-demand startups, Uber’s tumultuous 2017 has seen the company’s fortunes shift almost overnight.

Scandal after scandal brought accusations of everything from misogyny to intellectual property theft. This has turned the executive ranks of the world’s most valuable private startup into a revolving door. An exodus of senior leadership was capped by an investor revolt against co-founder and CEO Travis Kalanick, who had been virtually synonymous with the company and its famously aggressive culture.

New chief executive and former Expedia CEO Dara Khosrowshahi is just weeks into his new role, but faces pivotal decisions on how best to repair the company’s battered image and right the ship strategically. With a stated target of taking Uber public within the next 18-36 months, Khosrowshahi must strike a balance between financial discipline while also maintaining the growth and opportunity narrative that seduced investors and helped give Uber its lofty valuation.

Under new management, Uber’s strategies in both international markets and key fields of research like autonomous vehicles are open to revision. Key takeaways from our analysis focus on the company’s major initiatives:

- Balancing “paying the bills” and “big shots”: Uber’s new CEO committed to both instilling financial discipline ahead of a potential IPO and remaining invested in major forward-looking initiatives (such as autonomous vehicles). Aside from the considerable task of repairing the company’s damaged image and culture, finding a balance between these goals will be his major challenge going forward.

- Uber rethinks global strategy: Uber’s growth ambitions have begun shifting away from the pugnacious, attack-on-all-fronts strategy and indiscriminate spending of its earlier years, although the company’s latest financials continue to show a growing top-line as well as considerable cash burn. Our jobs listing analysis reveals that the company is still actively hiring in India, Brazil and Mexico. However, with a stated vision of taking Uber public within the next 18-36 months, Khosrowshahi may look to further narrow the focus on Uber’s efforts abroad to rein in money-losing efforts. Southeast Asia is one hotly-contested region where the company is spending heavily against the well-financed Grab and Go-Jek.

- Recent dealmaking focuses on divesting costly regional operations: Uber has withdrawn from its China and now Eastern European operations, retaining a significant stake in both while ceasing involvement in day-to-day operations. The company has now established a template that it can return to should it decide to draw down losses in other geographies.

- M&A to date has emphasized mapping and AI/AVs (autonomous vehicles): A late entrant into the now-fierce race to develop AVs, Uber has turned to M&A to bridge the gap in related competencies such as mapping and artificial intelligence. Its highest-profile deal to date was its acquisition of self-driving truck startup Otto, headed by Google Self-Driving Car (now Waymo) veteran Anthony Levandowski. That acquisition has led the company into a potentially devastating lawsuit with Waymo.

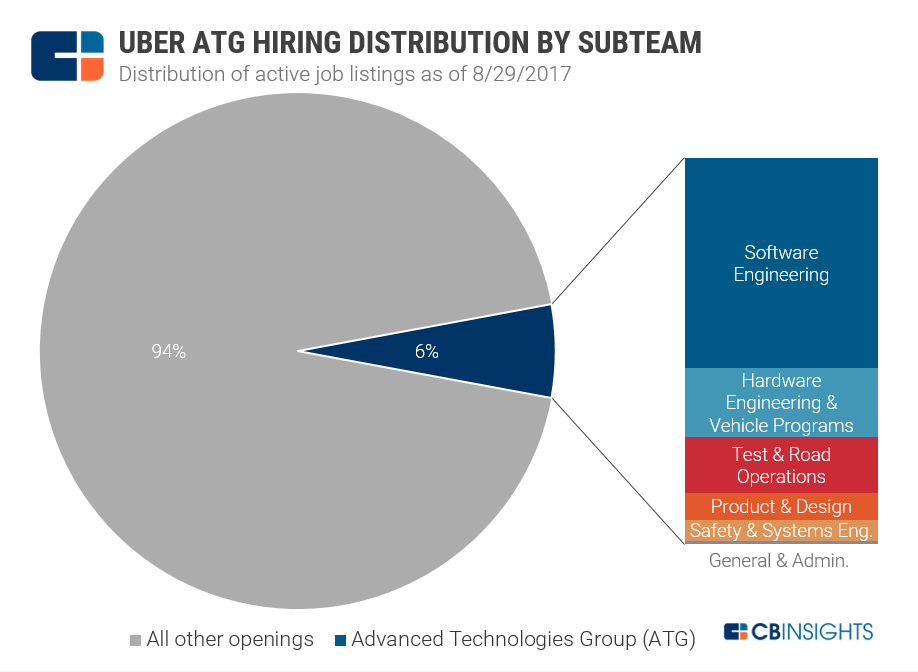

- AI, AVs remain a priority: Despite the upheaval in the wake of Waymo’s lawsuit, Uber is still hiring actively for its autonomous vehicle development group (Advanced Technologies Group or ATG). The unit comprises 6% of Uber’s total job listings, with the company seeking talent in the white-hot field of autonomous vehicle engineering. Uber also added a prominent AI researcher to lead a new ATG self-driving team. However, the unit’s long-term future is in doubt, with the Waymo lawsuit a looming threat and ATG requiring a sizable and sustained financial investment.

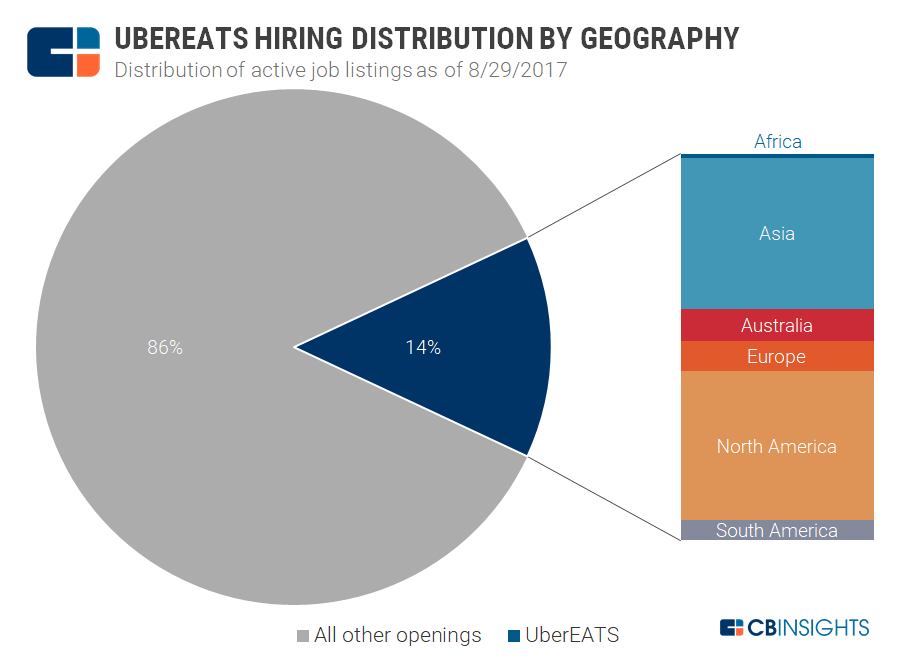

- Uber scales back other side ventures, focusing on food delivery: Outside of its core ride-hailing business, the company has retrenched in its once-hyped UberRUSH courier service effort, focusing on meal delivery platform UberEATS instead. The company continues to push UberEATS into new markets. Uber is also pursuing significant talent to support its food delivery service; 14% of the company’s open job listings mention UberEATS in the title. Uber has also recently launched its Freight service targeting the trucking brokerage market, but the new initiative has yet to gain meaningful traction.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Background on Uber and its new CEO

- Financials & valuation

- Deals: Acquisitions & investments

- Competitive landscape and a word on SoftBank

- Patent data analysis

- Uber initiatives by sector

- Final words

BACKGROUND ON UBER AND ITS NEW CEO

Though a surprise pick for the position, industry observers have generally praised Dara Khosrowshahi’s appointment, variously noting his experience helming a travel aggregator as well as overseeing a turnaround as Expedia’s chief executive. Expedia was losing share to competitors like Priceline when Khosrowshahi assumed the helm in 2005. The company was criticized for passing on an early chance to acquire Booking.com, which was acquired by rival Priceline and went on to become the world’s largest hotel booking site.

However, Khosrowshahi was willing to commit to long-term fixes, including migrating Expedia’s disparate brands to a common tech platform and recognizing the need for Expedia’s business model to evolve (from its preferred “merchant model” where it bought blocks of hotel rooms, to a hybrid model with the newer, lower-margin “agency model” pioneered by Booking.com in which platforms act more as intermediaries). Not coincidentally, this is more like Uber’s marketplace model.

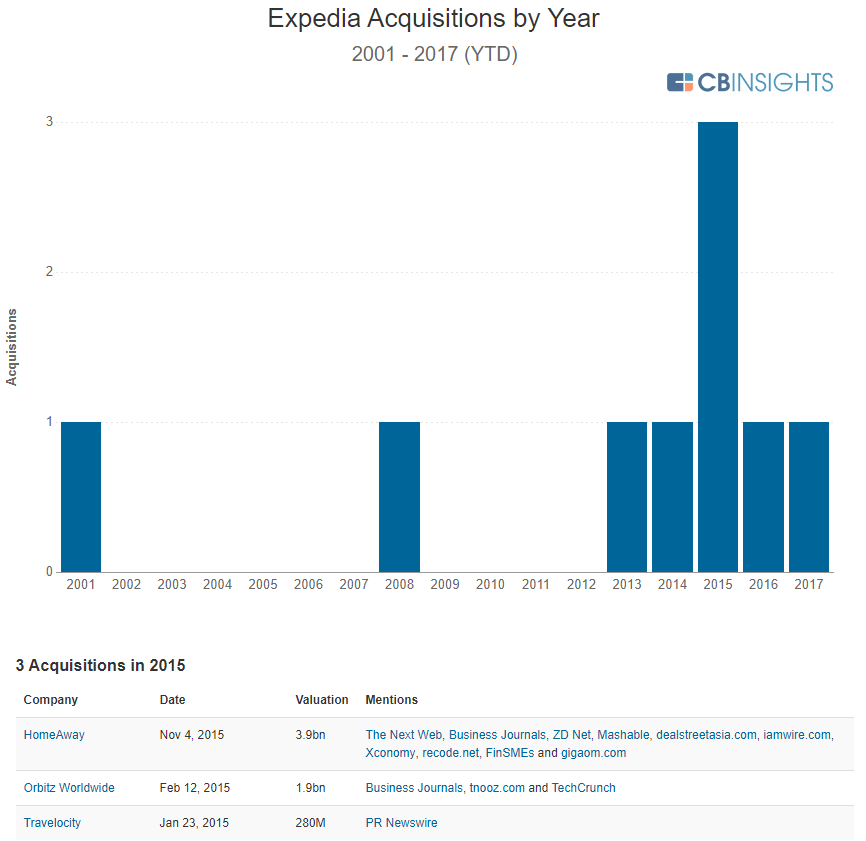

These efforts have undergirded Expedia’s recent uptick in acquisition activity, visualized below with our Acquirer Analytics tool. The company has made at least one purchase annually since 2015, and made three major acquisitions in 2015 alone:

(Clients can click here to browse Expedia’s rise in acquisition and investment activity.)

Khosrowshahi’s efforts resulted in the company more than quadrupling its gross travel booking value and doubling its pre-tax earnings under his leadership. Uber’s stakeholders are no doubt hoping that Dara-the-dealmaker will be able to lead another successful turnaround. He will likely have the missed Booking.com in mind as he weighs risk against reward for Uber’s future opportunities.

It’s worth mentioning that Uber also passed on a chance to merge with or acquire a major competitor: domestic rival Lyft offered to merge with Uber in 2014 for a share in the combined company, but talks broke down after Kalanick refused to budge on the share offered to Lyft (as Brad Stone writes in The Upstarts). Uber was again named as one of the potential buyers that Lyft had sought for itself in 2016, to no avail, according to the New York Times.

Though Uber still dwarfs Lyft by a considerable margin, the latter’s increasing US market share and partnerships in the autonomous vehicle space represent a growing thorn in Uber’s side. If Uber were able to strike a deal with its competitor under its new CEO, it would able to draw down its domestic US spending in a major way to focus on international efforts and frontier initiatives like autonomous vehicles.

Although this teardown will primarily focus on data points around Uber’s business strategy, it goes without saying that Uber and its new CEO face cultural and legal issues almost too numerous to list that have negatively affected the company’s prospects and investor confidence. Moreover, its guiding principle to date has been Kalanick’s mantra of “growth above all else,” which has defined the company to date not just culturally but also strategically (and so will resurface throughout our analysis).

The company’s alpha-male, growth-at-any-cost mentality and willingness to skirt regulatory and ethical boundaries arguably enabled it to crack open stagnant taxi and transport markets in the first place, attracting unprecedented amounts of capital in the process. In the same vein, a good deal of Uber’s self-made crises can also be traced to the institutionalization of these traits. This double-edged sword mirrors Kalanick mentor Mark Cuban’s description of the former CEO, saying in a New York Times interview:

“Travis’ biggest strength is that he will run through a wall to accomplish his goals. Travis’ biggest weakness is that he will run through a wall to accomplish his goals.”

Taken to their extreme, these philosophies have manifested themselves in the company’s Greyball tool for deceiving law enforcement, disregard for California DMV regulations for autonomous vehicle testing, and near-eviction from Apple’s App Store, among many other scandals. Allegations of pervasive sexual harassment and discrimination have also come to light, most notably from former engineer Susan Fowler.

It is worth noting that many of these issues are not wholly new: Uber’s abuse of its “God View” tool was first reported on 2014, as were sexist remarks from Kalanick and general knowledge of the company’s less-than-scrupulous business practices and sometimes insensitive treatment of drivers. However, for years these issues failed to slow Uber’s growth and fundraising momentum, as investors eagerly piled into technology’s hottest company. For longtime Uber watchers, 2017 was the year these issues came to a head with material impacts on the company’s business and investor outlook.

Active lawsuits and investigations involving the company include Waymo’s suit for intellectual property theft (which will go to trial), early investor Benchmark’s suit to remove Kalanick and three related seats from Uber’s board (which has been sent to arbitration), and a DOJ foreign bribery law probe, just to name a few.

Finally, Uber has also toed the line with the cutthroat competitive tactics it has employed against its rivals. These include Uber’s SLOG program for undermining competitors and its “Hell” program exploiting a Lyft vulnerability to track its opponent’s drivers. While these tactics are ruthless and have often been grouped together with the company’s other unscrupulous practices, their legality is undetermined. The FBI has begun investigating the software, although a lawsuit over the “Hell” program was recently dismissed in California federal court.

Khosrowshahi now faces the significant challenge of reforming Uber’s culture; former Attorney General Eric Holder’s investigation into the company resulted in a lengthy list of recommendations. Aside from extricating Uber from these many scandals, the company’s new chief executive must tackle a range of serious business challenges. One fundamental issue is replenishing the depleted ranks of Uber’s senior leadership:

Chief among these is Uber’s vacant CFO position, which has become a sore subject with some increasingly uneasy investors (Benchmark singled out the issue in its lawsuit against Travis Kalanick). The company has technically been without a CFO for over two years, a nominal head of finance Gautam Gupta departed for Opendoor in May. A CFO would play a critical role in preparing for an eventual IPO, which Travis Kalanick famously thumbed his nose at the thought of pushing forward:

“I say we are going to IPO as late as humanly possible. It’ll be one day before my employees and significant others come to my office with pitchforks and torches. We will IPO the day before that.”

By contrast, by his first all-hands meeting at Uber’s helm, Khosrowshahi had already floated the potential goal of taking Uber public within the next 18 – 36 months. The company has begun more regular, though still selective, financial disclosures over the past year. According to Axios, its latest Q2 2017 figures show continued top-line growth, with gross bookings up to $8.7B and adjusted net revenue hitting $1.75B (both roughly doubling year-over-year).

These figures do encompass the period of a large number of Uber’s scandals from earlier this year and the #DeleteUber campaign, but do not cover Kalanick’s departure and board civil war in Q3 2017. Uber’s adjusted losses, though narrowing, are still considerable and also exclude stock compensation, which the company is known for paying out generously in lieu of high cash salaries. Uber burned roughly $600M in cash through the quarter, with its total cash holdings down to $6.6B from $7.2B at the end of Q1 2017.

Coming back to Uber’s growth-obsessed mantra, the numbers reflect that the company has done well by this criteria, with its central ride-hailing business continuing to expand. The company’s booming top-line speaks to the still-considerable strengths of the company and opportunity ahead of it.

Though its product has evolved over time, from a tactical standpoint Uber has largely stuck to the same aggressive playbook: flooding new markets with incentives to recruit a critical mass of drivers and using subsidized fares to lure in riders. (Critics have labeled this as venture-financed predatory pricing, with the company often steamrolling regulators and misleading drivers in the process.)

Tracing this back to Uber’s overall strategy, last September Ben Thompson of Stratechery voiced concerns over Uber’s strategic finesse should the company meet an obstacle too stubborn to be overcome by the brilliance of its product-market fit and executional prowess:

“I do worry about this potentially fatal flaw: when and if Uber encounters a problem that requires more than simply hustle and execution, does their executive team have the temperament, strategic mindset, and deep-rooted understanding of their customer base to make decisions that aren’t so easily swept under the rug of product-market fit?”

With thorny questions surrounding Uber’s scandals, in addition to its plans for profitability, autonomous vehicles, international expansion, and beyond, perhaps it’s true that the company can no longer afford to simply be operationally brilliant yet strategically lacking. Khosrowshahi has acknowledged Uber’s multiple priorities, one being instilling financial discipline to “pay the bills” and the other being to “take big shots” and build for the future.

While it is too early in Khosrowshahi’s tenure for meaningful strategic changes to have taken hold, the company has already pruned its worst loss-making ventures and refocused its business both geographically and organizationally. We’ll explore those moves and other potential targets for Khosrowshahi in the sections ahead.

JOB LISTING ANALYSIS

For a view into Uber’s organizational priorities and growth areas (both geographically and vertically), we analyzed the company’s open job listings as of 8/29/2017. Note that these listings are for Uber corporate, and exclude listings or openings for the hundreds of thousands of driver positions available at the company worldwide.

The following graphic shows the distribution of Uber’s over 1,900 open job listings by team and subteam, where available. Click on the image to enlarge.

Operations

As mentioned above, Uber’s traditional strategy has historically emphasized growing and optimizing the supply side of their two-sided marketplace (that is, its network of drivers). The company’s billions in losses stem in large part from its spend to recruit and retain its drivers, a basic formula Uber has stuck to in both established markets like the US and areas of opportunity it has targeted internationally.

It’s not surprising, then, that the boots-on-the-ground work of launching, scaling, and maintaining operations in markets across the globe between the Operations & Launch and Global Community Operations teams accounts for over a third of Uber’s active job listings at 38.3%. These teams are on the front lines of Uber’s interactions with its “driver-partners” (in company parlance) and riders.

Engineering and product

On the general engineering and product side, Engineering (14.7%), Product (4.4%), and Design (3.1%) collectively account for roughly a fifth of the company’s openings. Peeking into Engineering subteams reveals a push on data science and mapping talent, both of which have been points of emphasis for the company.

Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group (ATG) is the Uber unit attracting the most media attention (and legal scrutiny), primarily for its work on self-driving vehicles spanning both passenger cars and trucks. The company’s recruiting efforts for ATG are apparent, with nearly 6% of its open listings filed under the unit (or just over 100 jobs). We’ll be diving into detail on ATG later on, but Uber’s job listings show ongoing recruiting efforts for deep learning and autonomous vehicle experts, among the most in-demand engineering roles in contemporary tech. Despite the legal specter hanging over the group, Uber is still investing in its autonomous vehicle efforts for the moment.

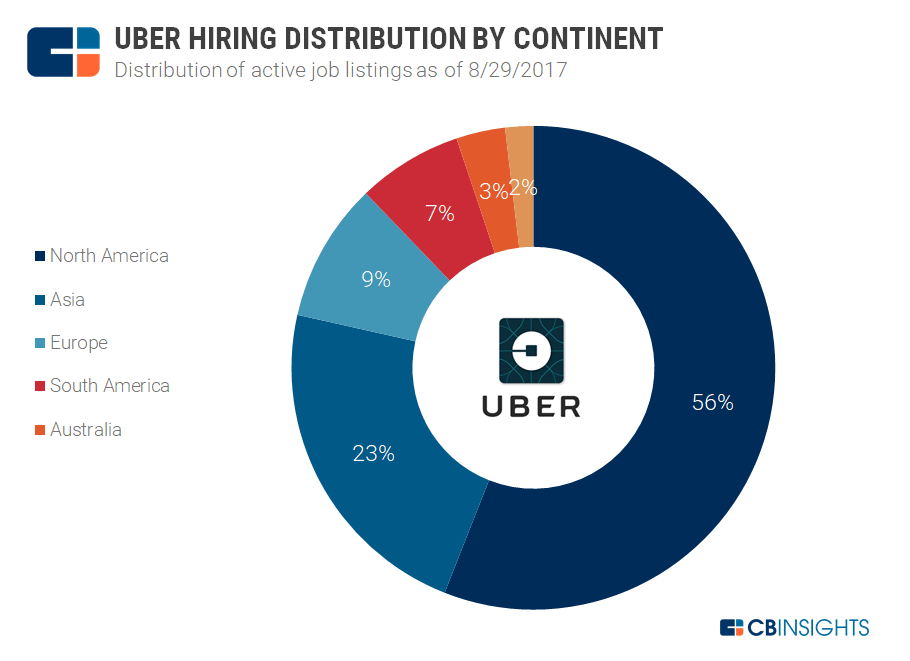

Looking at the geographic spread of Uber’s roles, generally, over half of the company’s open positions are based in North America. Asia represents just under a quarter of its listings, followed by Europe and South America.

Diving into specific countries, the US accounts for the lion’s share of roles as expected, with 48.6% of Uber’s open listings in its home country. We also analyzed the top ten ex-US countries where Uber is seeking talent:

Notable for their absence are markets such as China and Russia, evidence of Uber’s retrenchments abroad. The company’s August 2016 sale of its China unit to Didi Chuxing marked a sudden reversal in what had been a stubborn win-at-any-cost philosophy that cost Uber and its competitors billions (more on those deals in a moment).

Instead, Uber’s new international strategy now involves a more targeted approach, with a particular focus on developing markets. Uber and its rivals sense an opportunity to “leapfrog” the traditional vehicle sales model as consumers in these markets grow wealthier, pushing their ride-hailing and fleet-based services where ingrained cultures of individual car ownership have not been established. With ambitions in logistics services and transportation beyond just ride-hailing, these players are also referred to as transportation network companies (TNCs).

These international growth priorities are evident in the graphic, with India ranking as the non-US country with the most open job listings at nearly 8% of the total (or 150 jobs). Uber is also aggressively seeking talent in Southeast Asia, with Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines all making the top 10. Outside of Asia, Uber is also recruiting heavily in Latin America, with Brazil and Mexico collectively representing over 10% of the company’s open positions.

Uber’s SVP of Global Business highlighted India, Brazil, and Mexico as Uber’s top priorities; indeed, these three countries rank as Uber’s top 3 ex-US destinations in our jobs listing analysis. (We’ll cover that later on, with a deep dive on the stiff competition Uber faces from well-financed, home-grown rivals across these regions, including Grab in Southeast Asia, Ola in India, and 99 in Brazil, and more.)

Meanwhile, hiring in Uber’s traditional overseas headquarters of Amsterdam remains significant, representing 4.4% of its total. However, Uber’s European job listings in aggregate represented just under a tenth of its total, with the company listing more openings in emerging Asian markets and its home North American market.

Also not highlighted here is the Middle East and North Africa, another growth market where another ride-hailing competitor (Careem) has raised over a half-billion in capital. Egypt ranks just behind Japan for 11th place among Uber’s top ex-US hiring destinations, with 1.1% of the company’s open job listings.

FINANCING & VALUATION HISTORY

Uber has reached a level of mainstream consciousness uncommon among private startups, not just for the ubiquity of its service but also the vast sums of capital it has raised at eye-popping valuations. Our funding and valuation data reflects Uber’s meteoric rise since its March 2009 founding as UberCab (note that funding raised specifically for Uber’s China operations is broken out separately here):

(CB Insights clients can click here to access Uber’s profile and directly view all of its financing, investor, and valuation data.)

Growth was especially dramatic in the early- to mid-decade, culminating in Uber raising upwards of $6B in capital in 2016 alone. With Uber’s cap table crowded with dozens of investors and employees tied to famously restrictive “golden handcuffs” until recently, Uber has looked beyond standard equity financing to avoid further dilution for its shareholders. One of the company’s last major financings was a $1.15B leveraged loan in July 2016, arranged by four banks including Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. Uber is said to be paying a yield of roughly 5% on the loan, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Uber has tapped countless sources of capital to amass its war chest, and thus sports one of the most diverse investor networks of any private venture-backed company. We used our business social graph to highlight four key groups of Uber backers:

The company is famous for its clutch of early angel and VC investors, which the company has likewise lifted to stardom; Uber’s meteoric rise in valuation could single-handedly return the fund for these VCs, and generate a fortune for early angels. Crucially though, many of these returns are still on paper, with most investors not seeing any liquidity beyond secondary market transactions. Investors have been rattled by their inability to lock in returns, combined with the uncertainty now surrounding the company. This friction has contributed to ugly confrontations like Benchmark’s ongoing lawsuit against Kalanick (as disclosed by the firm’s complaint, Benchmark holds a roughly 13% equity stake, with Kalanick currently holding around 10%).

Veteran VC and longtime Uber champion Bill Gurley departed the company’s board in late June, after leading the push to pressure Travis Kalanick into his resignation. His board seat was filled by Matt Cohler, another general partner at Benchmark, but the firm remains in an uncomfortable position that has drawn ire from both other Uber investors and the venture industry as a whole. Shervin Pishevar, another early Uber backer, is now leading a coalition of investors pressing Benchmark to sell its Uber shares and leave the company’s board.

However, this controversy does highlight a growing concern within the investor community, as startups (particularly highly-valued unicorns) continue to stay private longer with multi-billion-dollar late-stage financings and access to diverse sources of capital, while early backers see limited liquidity despite enormous paper gains. In some ways, Uber has been the banner-carrier for this movement, with the company raising billions from investors like mutual funds and the Saudi sovereign wealth fund that aren’t typical private market investors, enabling Kalanick to avoid taking the company public.

Indeed, legendary VC Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures sided with Bill Gurley on founders’ and management teams’ fiduciary responsibilities:

“I agree with Bill Gurley on this. [Uber] should be a publicly traded company. When you take money from me, am I getting money from you? You have a responsibility to give me my money back sometime. You can’t just say f— you. Take the g—— company public.”

Another notable investor is GV (formerly known as Google Ventures), which first invested in Uber’s 2013 Series C alongside TPG. Longtime Alphabet exec David Drummond joined Uber’s board as part of the investment, but departed the position in late 2016 over a conflict of interest. Drummond had been “shut out” of meetings as Uber’s autonomous vehicles ramp-up brought intensifying competition with the Google Self-Driving Car project (now Alphabet company Waymo).

Since gorging itself on new capital in 2016, developments on the fundraising front have been quiet since the company’s Uber China divestment last August. Although the company still holds more than $6B in cash, there are signs that Uber’s business challenges and endless scandals have weighed on investor confidence in 2017. Uber’s mutual fund backers, which regularly disclose their private company valuations, have become the most outwardly visible indicator of this, as some recently marked down their Uber positions by up to 15%.

Potential new investors on the horizon include previously-mentioned SoftBank (which has already secured stakes in nearly all of Uber’s major rivals as well) and Dragoneer Investment Group, which are both said to be weighing a flat round, according to Bloomberg, that would bring Uber up to $1.5B in new capital, while also buying out up to $10B from the company’s existing shareholders. This deal would shake up the status quo considerably, as discussed in our analysis of SoftBank further below.

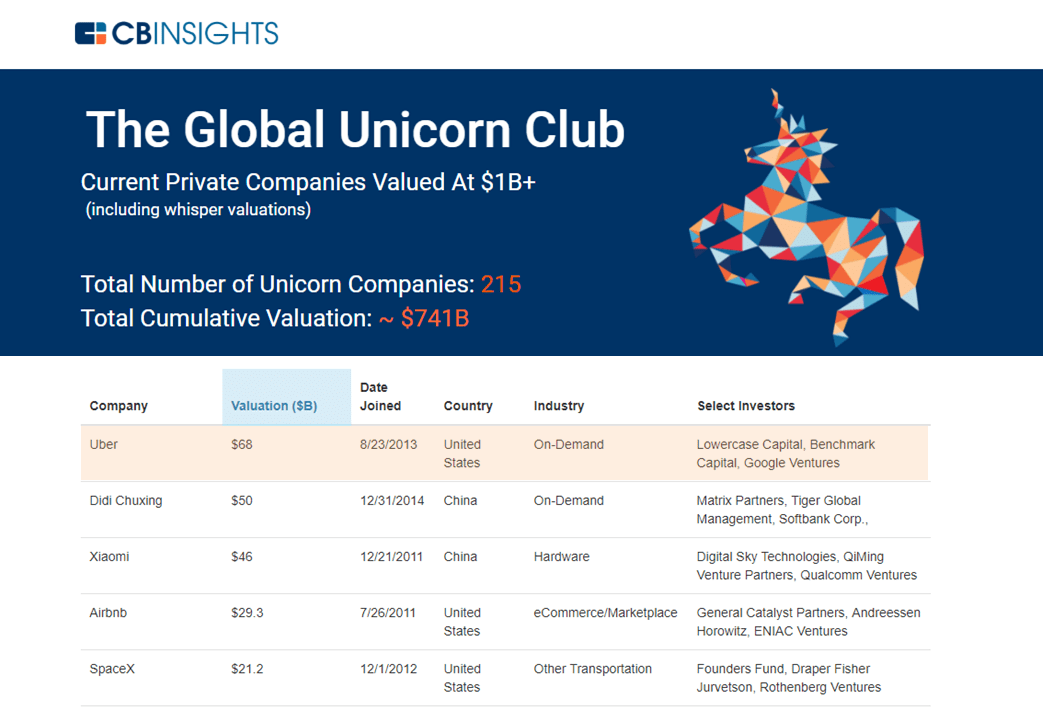

Despite not raising any significant disclosed funding in over a year, Uber still sits atop our unicorn tracker as the most valuable private VC-backed startup in the world:

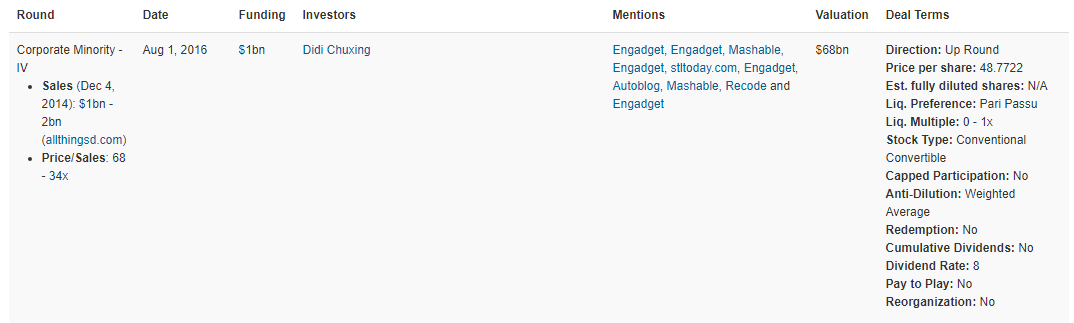

Chinese counterpart Didi Chuxing ranks among the few unicorns with a comparable valuation, last pegged at $50B as of Didi’s mammoth $5.5B raise in April 2017. For its part, Uber’s most recent $68B valuation dates to over a year ago, when Didi Chuxing itself invested $1B in Uber as part of the Uber China exchange (more on Uber’s divestitures below).

Though our analysis of liquidation terms has found a recent resurgence in investor-friendly senior liquidation preferences, our enhanced deal terms and valuation data shows relatively vanilla deal terms on this round, with a 0-1x liquidation multiple and pari passu preference. However, given the leverage that Uber has historically commanded over investors, it’s not surprising that Uber has been able to raise on largely favorable terms.

Clients can see more on divestitures below.

DEALS: ACQUISITIONS & INVESTMENTS

In September 2014, then-CEO Travis Kalanick boasted about Uber’s commitment to non-acquisitive growth:

“Uber has not acquired a single company. We are focused on the product. We are in 45 countries. We haven’t spent time on M&A.”

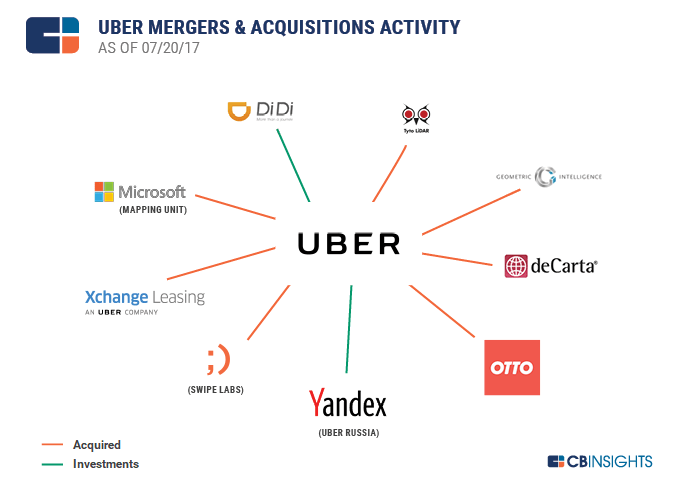

That era of Uber’s history is over. Uber recently completed its tenth major transaction as an investor with the acqui-hire of the team behind social app studio Swipe Labs, a deal that came less than a week after news of Uber’s deal with competitor Yandex Taxi, in which Uber ceded its Russian operations to Yandex in exchange for a 36.6% stake in a new joint company (created from their merged assets in the Russia market).

Uber started acquiring and investing in startups in Q1’15, and nearly every deal has had notable consequences for the business, including:

- Patent acquisitions (and lawsuits)

- Market share concession

- Business-unit creation and management shifts

We used our data to take a closer look at the company’s M&A history to analyze how Uber has behaved as a strategic investor.

Mapping has been a key focus, with Uber acquiring deCarta back in Q1 2015. The deal bolstered Uber’s mapping and navigation functionality, but it also kept deCarta’s patents out of the hands of Google, Apple, and other tech giants with aspirations in autonomous vehicles (AVs).

Uber followed up the deCarta acquisition by purchasing Microsoft’s Mapping Unit in Q2’15. The deal brought 100 of Microsoft’s engineers (as well as its data center and licensed intellectual property) in-house to Uber. As a result of the deal, Microsoft confirmed it no longer collects its own mapping data. In July 2016 Uber was said to be investing a further $500M to enhance its mapping system. Uber’s mapping vehicles have ranged as far as Singapore.

Uber has also taken a minority stake in an Indian company, plugging $6.4M into Xchange Leasing India in Q3’15, likely with an eye for boosting driver participation in India: partnering with Xchange gave Uber a way to offer affordable leases to drivers. Olacabs, Uber’s top competitor in India, announced a similar deal with an Indian automaker weeks before Uber acknowledged the investment in Xchange. Uber made a $30.2M follow-on investment in Xchange in Q3’16, but continues to battle Ola for market share in India. (For more on these top global ride-hailing firms’ investment and M&A strategies, click here.)

All of Uber’s systems- and talent-related acquisitions have sparked controversy. The company’s Q3 2016 acquisition of Otto—a self-driving truck startup founded by former Google engineer Anthony Levandowski—for $680M led Alphabet subsidiary Waymo to file a lawsuit in Q1 2017, accusing Uber of “calculated theft” of its AV trade secrets and technology.

Prior to the Waymo suit, in Q4 2016 Uber acquired Geometric Intelligence and the company’s 15 employees to form Uber AI Labs, a new artificial intelligence unit; the startup was working on making AI systems work with smaller sets of data than are typically required for object or scene recognition. Uber AI Labs saw a leadership change just three months after the acquisition: Gary Marcus, the former CEO/co-founder of Geometric Intelligence, stepped down from his role as head of Uber AI labs in March amid heightening criticism of Uber’s management practices, business tactics, and workplace culture.

Uber’s Q2 2017 acquisition of Swipe Labs—which built photo-sharing, chat, and video apps over its four-year history—was the company’s first acquisition since Travis Kalanick left the CEO role. Since the deal brings experienced engineering talent into Uber at a time when recruiting is almost certainly a challenge, we’ll be watching whether it’s the first of many acquisitions.

DIVESTITURES

Several of Uber’s moves have also narrowed the scope of its international operations outside North America. Since launching its China operations in 2014, Uber had been locked in a fierce price and subsidy war against Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache (the two later merged into Didi Chuxing, fka Didi Kuadi, to better combat Uber).

After burning over $2B in cash in two years of Chinese operations, Uber moved to sell its Uber China operations to Didi Chuxing in Q3’16. The terms allowed Uber to retain a 17.7% stake in the merged entity (with a 5.98% voting stake) in exchange for a $1B investment in Uber from Didi, with Uber becoming the largest single shareholder in its former rival.

Media reports characterized the deal as Uber’s “retreat” from China, and the divestment did mark a notable departure from the company’s commitment to winning wars of attrition. However, Uber was able to distance itself from the cash furnace that was its Chinese operation while retaining a sizable stake in any profits from the lucrative Chinese market. With Didi now valued at $50B as of its latest mega-round financing, Uber’s 17.7% share in the company is nominally worth over $8B.

In its most recent transaction, Uber also struck a deal with Yandex in Russia: with dynamics similar to the Didi Chuxing deal, Uber will invest $225M for a 36.6% stake in a new company created from Uber’s and Yandex’s assets in the Russia market. Yandex will invest $100M and own a 59.3% stake in the combined entity, with the remaining 4.1% held by employees. Once again, the company seemed to be looking towards narrowing its losses and geographic focus, while still retaining a stake in emerging markets (although it should be noted that the scale of the Didi and Yandex opportunities is vastly different).

COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE AND A WORD ON SOFTBANK

As recently as two years ago, it seemed that Uber was poised to dominate ride-hailing markets across the globe, flush with cash and riding the peak of the unicorn craze. The company stayed true to Kalanick’s aggressive growth philosophies, venturing into countries from China to Brazil.

With Uber’s retrenchment in China and Eastern Europe, the company has reversed course from indiscriminately pouring resources across the globe. Although the company’s war chest remains formidable, its competitors now sport impressive arsenals of their own. All of Uber’s well-capitalized rivals, both domestically and internationally, have raised significant new financing in 2017 as Uber itself has stumbled from crisis to crisis:

Uber’s battles with home-grown rivals in India (Ola) and Southeast Asia (Grab and Go-Jek) have been well-publicized, with its competitors also drawing multiple billions in funding. The threat to Uber’s traditional strategy of fighting wars of attrition in new markets has grown in tandem with these companies’ war chests. As seen in the jobs listing analysis above, these regions also rank among Uber’s most active in terms of open job listings.

Of these Southeast Asian competitors, Grab has raised progressively larger rounds, capped by a $2B Series G in July from Didi, SoftBank, and Toyota (as part of an ongoing $2.5B raise). Among Uber’s competitors, Grab in particular has invested aggressively in new markets, recently allocating $100M over the course of three years to shut Uber out of the recently liberalized (and rapidly digitizing) Myanmar.

By contrast, Ola has comparatively stumbled. After raising a $275M Series G in November 2015, the company did not see new capital until it received $330M from SoftBank in February 2017. The financing was a significant downround, in which Ola’s valuation was slashed from $5B to $3.5B amid competitive pressure in Uber and the broader slowing of venture investment in India.

Given Ola’s struggles, Southeast Asia is beginning to look like a more uphill battle than India. Grab has strengthened its competitive position in Southeast Asia, while another major competitor in Indonesia, Go-Jek (whose ride-hailing service was originally founded on ojek motorcycle taxis), is ramping up.

When speaking to Indian reporters in August 2017, Uber SVP of Global Business David Ritcher also made no mention of Southeast Asia, instead naming the same three countries as the top ex-US hiring targets we highlighted in our analysis above:

“There are three countries that we are betting on – India, Mexico, and Brazil. We have seen phenomenal growth in India, in July this year over last, we have seen 115 per cent growth.”

To be sure, Uber is still in a firm second place behind its Indian rival, but scaling back in one of its myriad areas of operation would allow it to concentrate its resources against select competitors.

SoftBank and Didi Chuxing have both become ubiquitous names on the cap tables of ride-hailing companies. Using the CB Insights Business Social Graph, we can visualize SoftBank and Didi’s various plays in the international ride-hailing market (each green line represents one deal):

SoftBank has participated in multiple financings to Uber’s three largest Asian counterparts, including Didi Chuxing itself. The conglomerate has also backed Uber’s chief Brazilian rival 99 (formerly 99Taxis). This is another emerging market that has become hotly contested, and Uber seems to be committing to the Latin American opportunity (recall that Brazil and Mexico, respectively, ranked as the second-place and third-place countries by share of open Uber jobs in our analysis above).

As mentioned above, SoftBank is now said to be strongly considering an Uber deal, with Recode reporting that talks have advanced under Uber’s new CEO. The potential arrangement is said to include both the sale of new shares (which would raise fresh capital for Uber) and the buyout of shares from existing investors, in a deal that could range up to $10B total. Earlier in August, the conglomerate had signaled interest in either an Uber or Lyft stake.

Whether SoftBank strikes an Uber deal or not, the firm looks to be making a blanket bet on the ride-hailing space as a whole. The generous sums of capital doled out by the firm could further extend these private companies’ runways and further distort the traditional private markets funding environment (investors are wary that the company and its $100B Vision Fund might do the same in other tech sectors). However, a potential deal is said to include a sizeable secondary market transaction, which could give some employees and early investors an opportunity to see liquidity. An infusion of new capital, combined with liquidity for early stakeholders, could reduce the need for Uber to go public and change its strategic standing yet again.

Didi has mutual stakes with SoftBank in all of the latter’s ride-hailing investments, in addition to its own investments in Lyft and Middle Eastern counterpart Careem Networks. The Chinese firm’s investment- and partnership-based approach to empire-building is a stark contrast to Uber’s strategy of direct invasions and competition. Prior to the Uber China-Didi deal, Didi had also led the formation of an “anti-Uber” alliance spanning its regional investment partners, although that coalition has fizzled since the Uber China detente.

In Europe, Uber has established a significant presence, but has also been shut out from markets like Denmark, Germany, and Hungary by regulations. The Daimler-backedmyTaxi service claims to be operating at a larger scale than Uber in Europe, while Daimler also recently invested in Via to bring that shuttle-based service’s operations to London. Gett and Taxify are also notable competitors. Given the patchwork state of European regulations and competitors, combined with the lack of a large primary opportunity and more mature market, it’s not surprising that Uber’s heaviest international efforts have focused on developing markets.

Finally, in the US, Uber’s dominant position has eroded as Lyft has battled back with generous subsidies combined with concerted marketing and partnership efforts. Lyft has also taken advantage of Uber’s tumultuous 2017, especially in the wake of the #DeleteUber campaign in the spring. Second Measure’s data on Uber’s US market share showed that figure falling from over 90% in 2014 to 74% as of August 2017, with a near 5% drop in the week of #DeleteUber alone. The company’s loss of share has come almost entirely at the hands of Lyft.

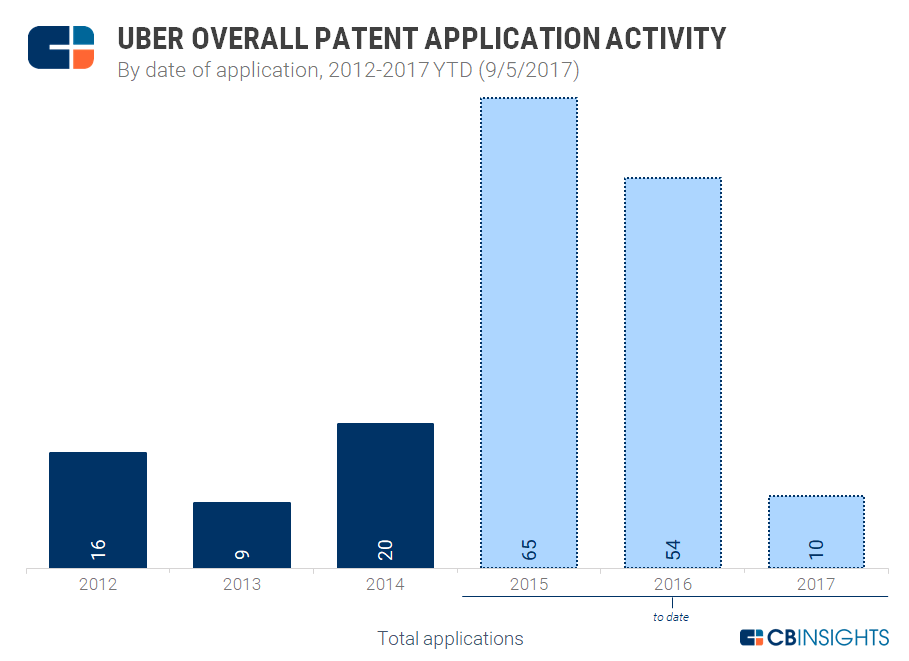

PATENT DATA ANALYSIS

Uber’s patent activity is predictably more sparse than that of giants like Google or Amazon. Nevertheless, the ride-hailing giant is growing more active in securing its intellectual property, particularly as it ramps up research efforts in frontier technologies such as autonomous driving.

Note: This analysis comes with a few caveats, primarily that the patent filing process involves a significant time lag before the publishing of patent applications. This delay can range from several months to over two years. We also focused on Uber proper for the purposes of this analysis, which would exclude any patents absorbed through external acquisitions not reassigned to Uber itself.

We also mined each year’s applications to tease out recurring keywords from the patent abstracts, using a significance weighting scheme to surface words and phrases. (Note that records prior to 2014 are likely complete, but analysis for the most recent years only includes applications published to date, subject to the USPTO review and publication process.)

While patents are still being released weekly, the ones that have rolled in from 2015 and 2016 highlight Uber’s intensifying focus on autonomous vehicles research following the formalization of its self-driving unit, seen in orange below. The company’s significant patent phrases highlight a shift away from building its core on-demand network (“demand service” and “transport service”) to autonomy and related efforts in mapping (highlighted in blue):

Clients can click here to search Uber’s autonomy vehicle patent activity; we’ve also highlighted specific Uber patents in our tracker of auto and logistics tech patents activity.

While this analysis concentrates on patents assigned to Uber proper, it goes without saying that the company’s acquisitions have brought Uber both additional intellectual property and serious allegations of IP theft. Waymo’s suit against the company alleged, among other things, that Otto co-founder Anthony Levandowski stole 14,000 confidential documents before leaving Google, enabling Uber to infringe on its technology patents—particularly that of Waymo’s proprietary lidar technology.

Levandowski has since stepped down from his role as head of Uber’s self-driving unit, but the suit remains pending. Otto’s acquisition of Tyto Lidar in Q2’16, in advance of Uber’s purchase of Otto, will likely play a role in the case. Court documents have revealed Waymo’s allegations that Levandowski personally owned and controlled Tyto during his tenure at Google; the company’s path to Uber is obscured by a number of shell companies.

Regarding Uber’s deCarta deal, reports show that the company transferred 7 patents to Google (related to matching mobile users and service providers, mobile advertising, and connecting mobile users based on degree of separation) and sold 6 to Samsung (related to mobile user notifications) prior to being acquired by Uber. At the time of Uber’s acquisition, deCarta owned 25 patents, plus 6 pending, covering various aspects of route planning, point-of-interest identification, and internet-based map searching.

UBER INITIATIVES BY SECTOR

AI AND AUTONOMY (ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES GROUP)

Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group is the company’s central hub for developing autonomous vehicle (AV), mapping, and safety technologies. Under Travis Kalanick, the unit ranks among the company’s foremost long-term priorities. Although Uber itself has long threatened the model of traditional auto OEMs, Kalanick echoed automotive executives in labeling AVs an existential threat to his business, in an interview with Business Insider:

“It starts with understanding that the world is going to go self-driving and autonomous… So if that’s happening, what would happen if we weren’t a part of that future? If we weren’t part of the autonomy thing? Then the future passes us by, basically, in a very expeditious and efficient way.”

This sense of urgency to build in-house AV competencies fueled aggressive moves that have landed ATG into several controversies. Chief among these is the aforementioned Otto acquisition and subsequent Waymo lawsuit. The case has become a potentially existential threat to Uber’s self-driving program (and even the company at large) should the process end with an unfavorable ruling, the worst-case scenario being a decision that Uber’s Otto acquisition was an orchestrated play for intellectual property theft.

The trial is a month out at the timing of writing, but Alphabet is not known for being particularly litigious – executives like Larry Page and Sergey Brin have long been philosophically opposed to excessive patenting and IP litigation for stifling the innovative spirit of Silicon Valley. Thus, eyebrows were raised when Waymo disclosed its suit in February 2017.

The original founding of ATG itself caused some ill will as well, with Uber essentially abandoning a partnership with Carnegie Mellon in favor of poaching many of its staff directly onto its team instead (the company’s original Advanced Technologies Center is located in Pittsburgh for this reason).

Despite the turmoil surrounding the team and company, Uber remains committed to its AV development for the moment, and is still actively listing open roles within ATG:

It’s notable that recruitment areas here span some of the most in-demand fields in tech, including deep learning, sensor fusion, and computer vision specialists (mostly within the Software Engineering subteam above). With AV engineers in short supply and a fierce recruiting battle raging, salaries in the field now range up into quarter- or half-million-dollar territory, and Uber’s worsening image had made finding scare talent even more difficult. The company also lists a handful of additional positions to expand its Testing & Road Operations subteam, which is now active in Pittsburgh, Phoenix, and San Francisco (the latter after initially flaunting California DMV regulations, only to draw a sharp rebuke).

Aside from passenger vehicles, Uber teased the new look of its autonomous trucking prototypes in July 2017, perhaps as a reminder that its trucking program remains active in the wake of Waymo’s suit. Notably however, the lidar sensors fitted to Uber’s rigs was an off-the-shelf design, rather than any of the in-house solutions that have been implicated in the Waymo suit. The ongoing process has revealed that Uber continues work on its own proprietary lidar solutions, including an upcoming unit that it claims is “vastly different” from Waymo’s.

The company has also committed to new executive hires to replace autonomous vehicle talent lost in the wake of Waymo’s lawsuit. In May 2017, the company hired Raquel Urtasun, a noted University of Toronto AI researcher, to build out a lab for AV research in Toronto. The unit will be the third ATG office, joining Pittsburgh and the Bay Area (Geometric Intelligence continues to serve as the company’s central AI lab).

Reports on Uber’s AV progress to date have been spotty, but internal documents leaked to Recode in March 2017 painted a less-than-ideal picture, with the company’s vehicles disengaging (with human drivers being forced to intervene) nearly once every mile. By comparison, Waymo’s disengagement rates had fallen to 0.2 incidents per 1,000 miles in 2016. Although these companies may be recording these statistics differently, the relative gap is still considerable.

Despite its reputation as a maverick, Uber had originally looked to collaborate with high-profile AV developers, including both Google/Waymo Tesla. The Waymo-Uber lawsuit has revealed documents that detail Kalanick’s attempts to forge a partnership with Google. Kalanick eventually met with Google’s CEO Larry Page, but talks fizzled out and the companies quickly became bitter rivals. The former Uber CEO also met Tesla chief executive Elon Musk to propose an AV partnership but was rebuffed on that front as well.

Demanding a heavy capital outlay over a long timeframe and faced with an uncertain legal future, ATG stands as one possible candidate for the company to reduce its cash burn. Outward-facing indicators (like Uber’s disengagement statistics and smaller test fleet) pegs the company’s efforts behind competitors; new management may choose to jettison the sunk cost if the program is deemed too far behind. It remains to be seen whether Khosrowshahi will come to see an in-house AV development team as an “existential” necessity in the same way Kalanick did, although the new CEO did commit to “taking big shots” (in addition to “paying the bills”).

As recently as last month, The Information reported that an unnamed automaker had approached Uber to buy its self-driving unit outright, which the company rejected at the time. Nevertheless, Uber is now said to be reconsidering the notion of entering joint ventures or partnerships to defray the costs of developing AVs. The list of candidates has narrowed, with Uber’s list of acrimonious relationships, and Lyft actively seeking AV partners with its open autonomy platform (and also kicking off its own AV development efforts).

However, the company did strike a January 2017 agreement with Daimler to deploy the automaker’s self-driving vehicles on Uber’s ride-hailing network. Other automakers with fewer ride-hailing investments and partnerships might also be candidates, with Ford being one example. Should Uber ultimately scale back its AV program, many startups and larger corporations are developing on autonomous systems for retrofitting onto existing vehicles or licensing for third-party use.

COURIER AND FOOD DELIVERY SERVICES (UBERRUSH AND UBEREATS)

Uber Everything, the company’s startup-within-a-startup, resembles units like Alphabet’s X for incubating experimental ideas. Uber Everything is more focused than Alphabet’s “moonshot lab,” with an emphasis on building on-demand services adjacent to Uber’s core ride-hailing business. As one employee put it, Uber Everything would be like the countless “Uber for X” startups inspired by the company, except incubated within Uber.

The unit incubated two new products that have since taken divergent paths: UberRUSH, its on-demand local delivery service, and UberEATS, the company’s meal ordering and delivery platform.

When UberRUSH debuted in 2015, the company hoped that its courier delivery service could leverage Uber’s driver network, tech platform, and deep pockets to replicate the success of its primary business. However, in early 2017 the company shuttered its UberRUSH service for restaurants, encouraging them to move over to UberEATS instead. The service’s website lists the same areas of operation (SF, Chicago, and NYC) as it did upon launch, and the company has barely a handful of job listings that mention UberRUSH by name.

Our cross-functional analysis of the nearly 2,000 job titles we collected revealed Uber’s priorities here. Nearly 14% of Uber’s active openings (or over 250 jobs) list UberEATS explicitly in the job title.

Uber faces stiff challenges here from other tech rivals, as dominant US player GrubHub Seamless recently acquired Foodler and Eat24 to further bolster its leading position. Amazon, too, may encroach further on the food meal delivery space following its Whole Foods acquisition. Internationally, Uber must contend with formidable local competitors across regions, much like its core ride-hailing market. These include Delivery Hero and Just Eat in Europe and Ele.me in China, just to name a few.

Despite this, Uber is actively seeking talent to expand UberEATS internationally; just 31% of its UberEATS-titled jobs are based within the United States, with the remainder spread across the globe. As with Uber’s job listings overall, India again appears as the most active country outside of the US. Beyond India, Singapore, Australia, and Mexico all rank among the company’s top current UberEATS hiring destinations. Uber is fielding nearly as many open UberEATS positions for Australia as it is for the whole of Europe combined.

OTHER INITIATIVES: FREIGHT BROKERAGE AND FLYING CARS (UBER FREIGHT AND UBER ELEVATE)

Uber’s brokerage efforts are still in their nascent stages, with Uber Freight having formally launched in May 2017 following a soft launch late last year. Its service aims to connect shippers needing to move cargo with truckers. The idea is not a new one, as our trucking market map highlights the considerable competition Uber faces in the broker space:

Uber Freight is rolling out in a handful of areas, including the Chicago area, California, Arizona, Georgia, and the Carolinas. The company listed 17 open positions with “Uber Freight” job titles as of 8/29/2017, showing ongoing recruiting but a gradual effort far from the ramp-up of other services like UberEATS (and another departure from the company’s signature aggressiveness).

Of note, Uber’s new CEO is an existing investor in Convoy, among the brokerage startups that has been referred to with the “Uber for trucks” moniker. Khosrowshahi may now need to divest his shares in the company due to a conflict of interest with Uber’s new Freight initiative.

Finally, one of Uber’s most fringe initiatives is its Elevate project, which aims to field on-demand urban transport with flying taxis. The company held a 3-day summit in 2017 around the topic, but listed almost no open positions explicitly for Elevate. It remains to be seen whether the company will be able to spread its resources across multiple engineering projects from autonomous cars and trucks to flying taxis, not to mention its global expansion efforts.

FINAL WORDS

Uber is very much at a crossroads as it seeks to leave the worst of its traits behind it, while carrying forward the vision of growth and boundless opportunity that initially defined the optimism around it. It seems unlikely that the company will able to continue investing scattershot across global markets and various projects, especially as Dara Khosrowshahi looks to get Uber’s finances in order.

There are potential parallels here to Alphabet, a tech giant obviously at a very different stage of maturity and financial health, but one that also saw new management (under CFO Ruth Porat) begin to rein in a sprawling web of business units and instill financial discipline across its many experimental initiatives.

Despite the negative sentiment towards the company, Uber’s basic financials and hiring data still show an organization that has the potential for rapid growth. Going forward, Uber’s greatest strategic challenge will be rewriting its playbook of venture-financed expansion to move towards a more profitable and sustainable model of growth.

via cbinsights